Costing methods are important to nail down. This is because each method can report very different profits and cost of goods sold (COGS), even when you calculate from the same stock levels and purchase prices. We’ve discussed FIFO (First in first out) and LIFO (Last in first out) costing methods in other articles, so now it’s time to discuss a third option, the moving average formula. The moving average formula is a solid choice for ensuring your costs are always up to date.

A moving average formula will generate a product cost that falls between what FIFO and LIFO would report. This can be very useful if it isn’t possible or feasible to deal with multiple costing layers.

Be sure to download our handy Inventory Formula Cheat Sheet. It has 7 of the most common inventory formulas all in one convenient location.

Download your inventory cheat sheet now!

The moving average formula doesn’t use costing layers

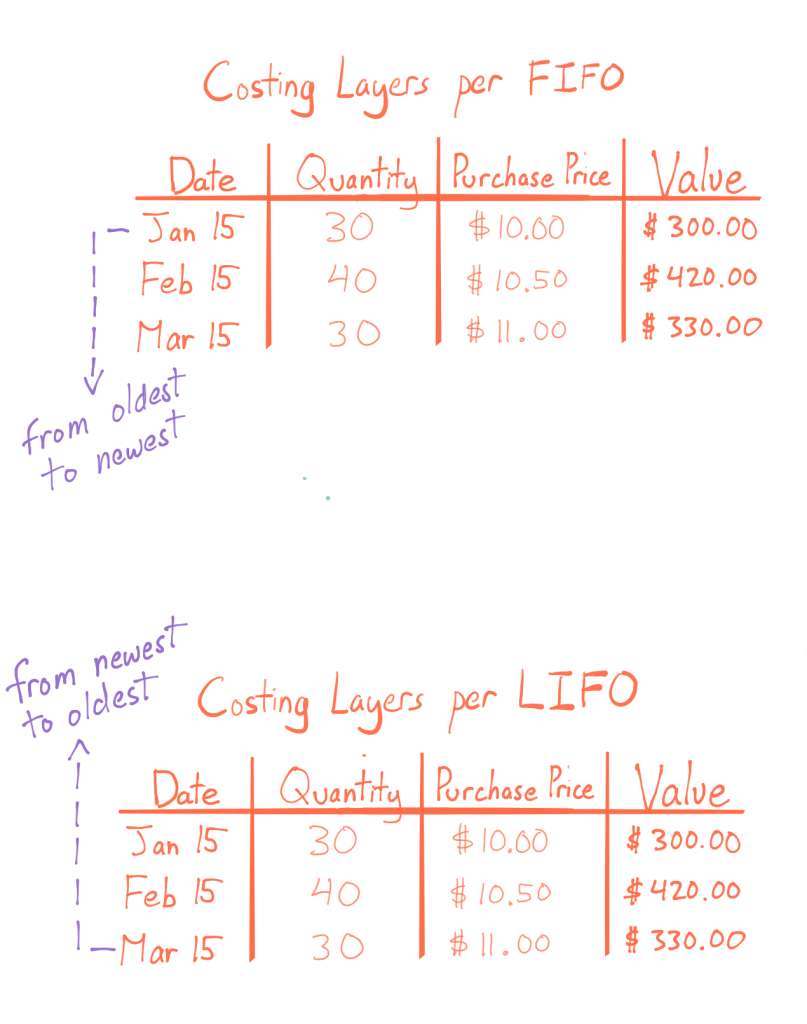

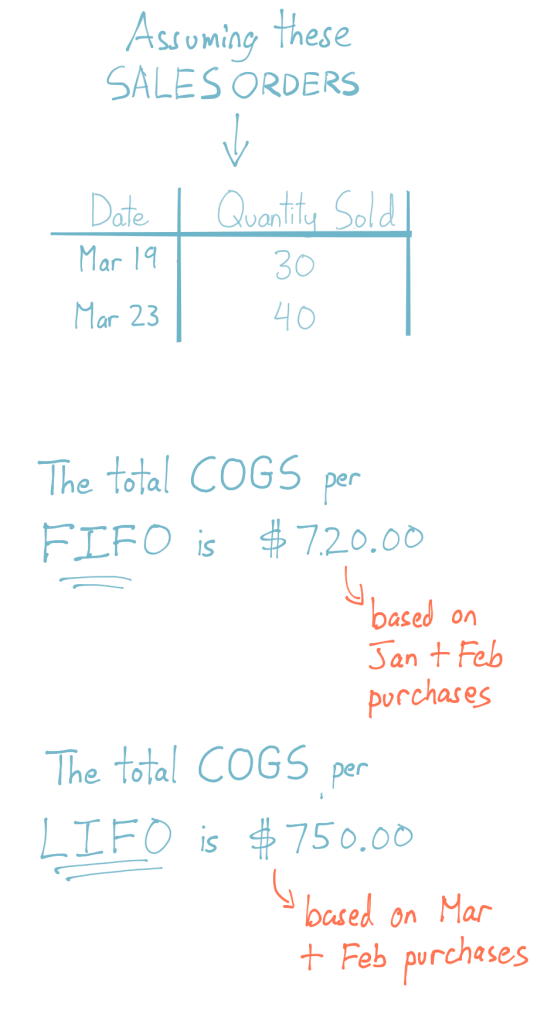

You might recall this table for Zealot lens purchase and sales orders, which we used to discuss FIFO and LIFO. We tallied the cost of goods sold for 70 units by finding the sum of different costing layers.

FIFO used January and February’s orders to derive COGS because it took from the oldest stock first. LIFO used March and February for COGS because it took from the newest stock first. Now let’s examine COGS by tallying the sale of 70 units on March 19 and March 23:

Whichever way you slice it, that’s two costing layers you have to account for when you sell those goods. Multiple cost layers can make it difficult to calculate profit or COGS. Especially when a sales order uses stock from different purchase orders (with varying layers of cost). The current example is neat and tidy because the sales orders use exactly two costing layers. However, you can often have sales orders that take all the Zealot lenses from January and just three from February. That would leave you with a partial cost layer from February that you still need to account for moving forward.

How to use the moving average formula

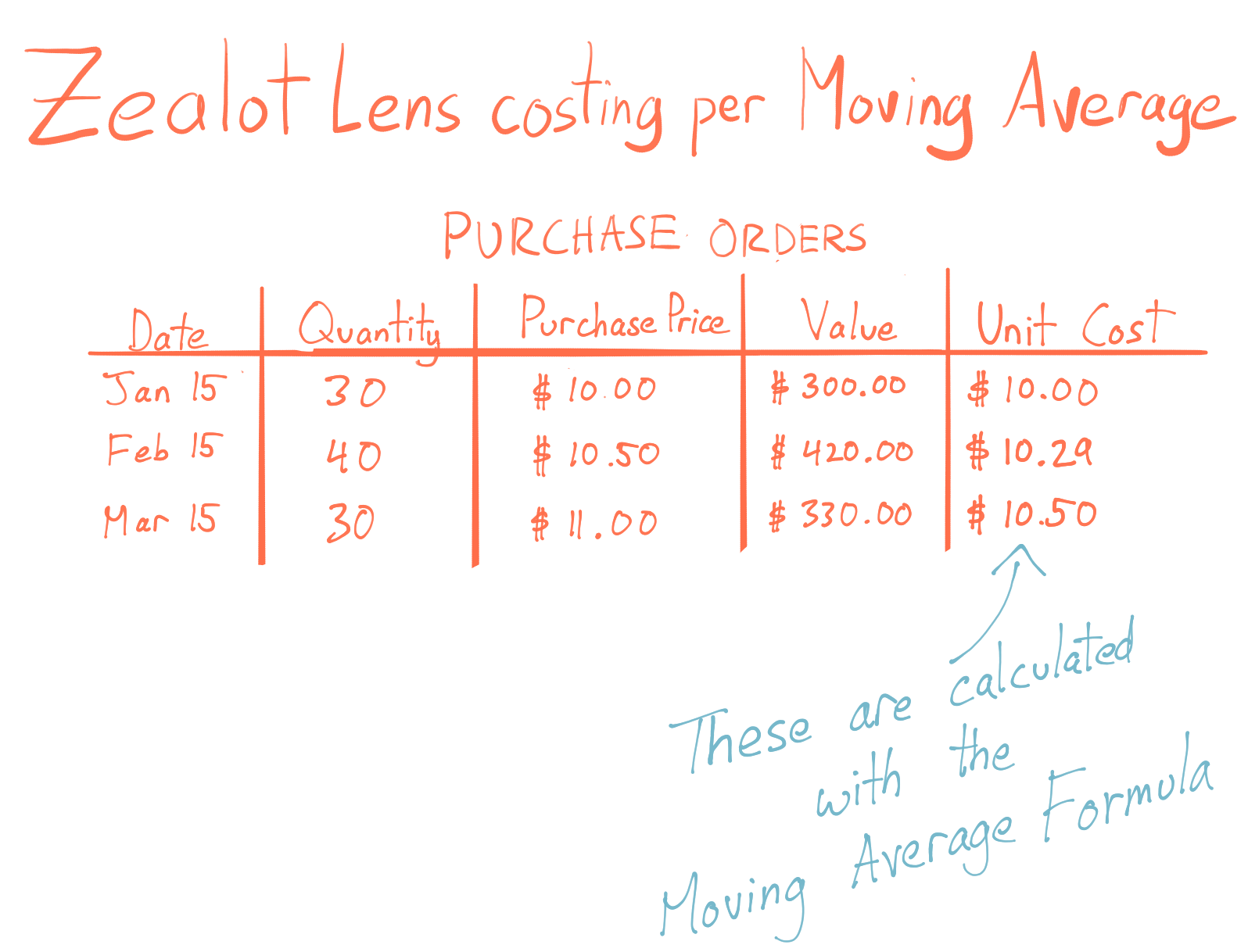

Using a moving average formula saves you from having to track any costing layers. Instead, you’ll re-calculate the average cost per unit each time you purchase more stock — hence the name “moving average”. Here’s the same set of POs for Zealot lenses, with an extra column for unit cost:

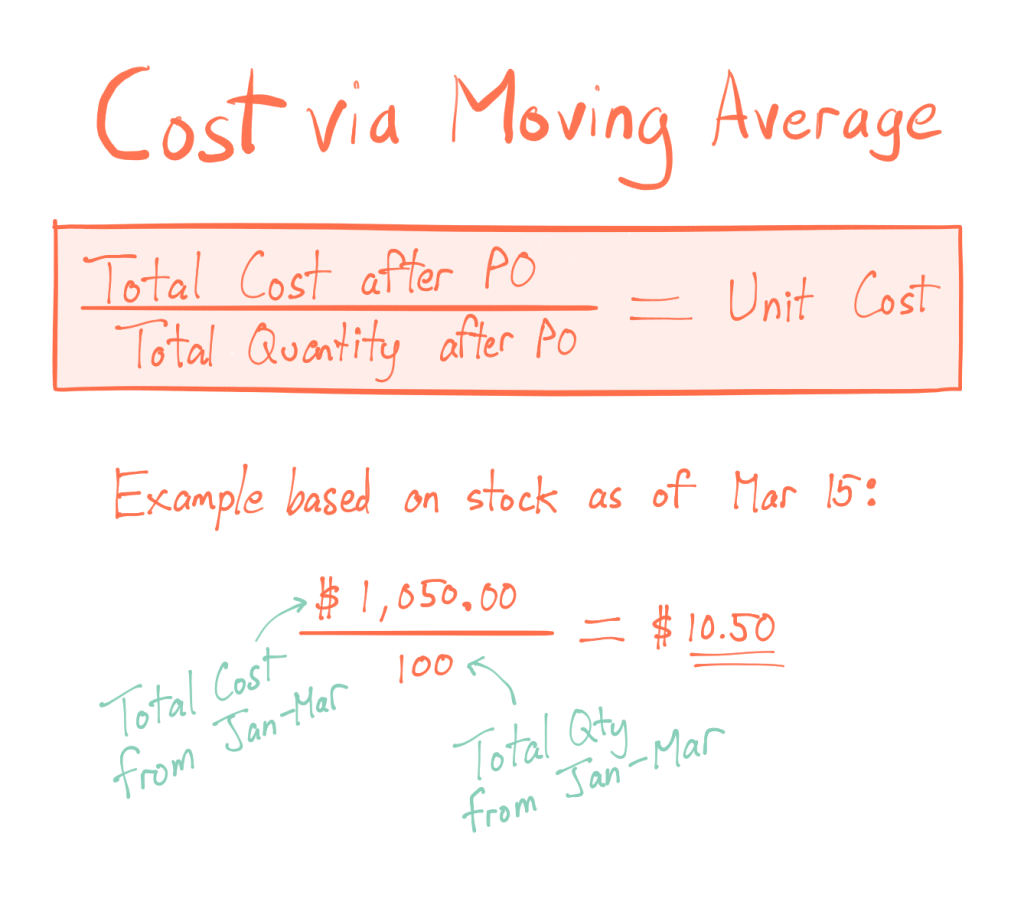

You base the unit cost on the value of incoming stock + the value of leftover stock from previous orders. Your total cost is the value of what you have left + the value of the newly received stock. You get unit cost when you divide the total cost after a PO by the total quantity after a PO. Here’s how to use the moving average formula to arrive at the unit cost of $10.50:

The big advantage of the moving average is that COGS becomes much easier to calculate. You would simply determine how much of a product you’ve sold and multiply that amount by your current unit cost. You’ll only have one unit cost to worry about because you’ll always recalculate unit costs after every PO. This makes it much simpler to track the actual cost of goods sold, regardless of whether you sell 10 or 100 products per order.

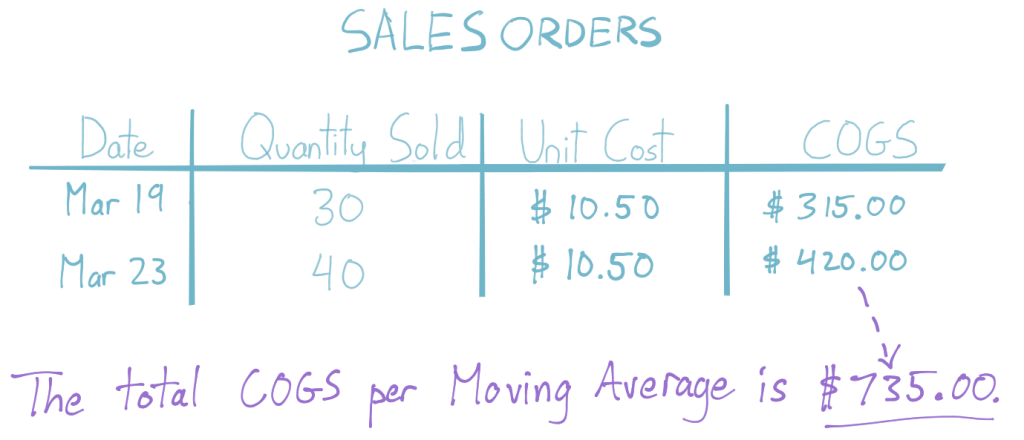

Now let’s go back to the sales orders of 70 units of Zealot lenses from earlier. This time we’ll calculate the COGS with moving average:

FIFO vs. moving average vs. LIFO

Using the moving average formula to derive COGS from Zealot lens sales, you can see that it falls between the figures that FIFO or LIFO report:

- FIFO reported a COGS of $720.00

- Moving Average reported a COGS of $735.00

- LIFO reported a COGS of $750.00

It’s important to remember that the cost of goods sold will not be identical when comparing FIFO vs. moving average vs. LIFO in a particular period of time, like a financial year. This can affect how much revenue your business ends up reporting, which affects how much tax you pay. Determining which costing method suits your business and sticking to it is essential.

Disadvantages of moving average costing

Although the moving average costing method is pretty widely used, there are some downsides that you should be aware of before you fully commit. Some of those are:

- Distorted data – Extreme fluctuations in prices can impact the validity of moving average costing. For example, if you were to buy some stock at a discount. This is why moving average costing isn’t the best for businesses that sell a lot of seasonal products. These products experience dynamic pricing, which changes drastically during the off-season, throwing off your data.

- Fluctuating profit margins – Since you continually adjust moving average cost with each purchase, your COGS and gross profit margins will both be impacted.

- Complex financial reports – Compared to other costing methods like FIFO and LIFO moving average costing can make financial reporting much more complicated. The reason for this is because each inventory’s value is continually changing. This makes it challenging to provide clear and concise financial statements.

Whatever costing method you decide to use should be based on what’s good for your specific situation. There really isn’t a “one size fits all” for businesses, but using moving average costing is a pretty good option.

inFlow Inventory makes moving average costing easy

Some businesses track their FIFO and LIFO costs on paper, but if you choose to use moving average, you’ll want software to help you keep all the math manageable. Excel can work if you have a formula to keep rolling the totals from a previous cell, but that requires consistent fine-tuning. inFlow handles all of these critical, continuous calculations on the back end so you can focus on other aspects of your business.

This method of cost tracking works very well for many small businesses. For this reason, we’ve made it the default costing method in our software (although you can change this). If you start using inFlow, it will automatically use the moving average formula so that you can see how unit cost has changed over time.

Hi! I’m going to use average moving method. Could you advise,how to calculate average cost if i have sales first than purchases?

Hi Liza,

This sounds like a situation where you are back-ordered or you have to specially order an item in. I think you would need to wait for the purchase order (PO) to arrive, and that would help you to establish your cost.

You can still use the moving average formula provided in the article, but with a slight modification.

Our original formula above tries to factor in existing stock, but you can’t do that in your example, because you sold your item on a sales order (SO) without having any in stock. You would have to create a new PO to actually get that product in so that your customer could take it.

So in cases where you have 0 or negative stock, I’d modify the formula to apply to your very next PO only:

Average unit cost = [Total cost of PO / Total qty ordered on PO]

Once you get back to having a positive amount of stock (over 0), you can go back to using the formula in the article.

– Thomas

Can similar items be reasonably grouped? For example if I have 2-3 types of necklace cords I use for making/selling pendants can I group these under “Necklace Cords” with an averaged price? I do many small batch and one-off projects and tend to buy a lot of different raw materials but in a fairly small number of categories.

Hi Dan,

If I understand that correctly, groiuping 2–3 different pendants would be calculating cost for a category or group. It’s fine to do that if they’re very similar costs and prices, but it’s not the same thing as identifying the moving average cost for one particular kind of pendant.

What about if I have incoming debits and credits and I need to find the latest value?

For example:

Description AMOUNT QTY

Credit -255.15 -1.000000

Credit -255.15 -1.000000

Credit -255.15 -1.000000

Credit -255.15 -1.000000

Debit 289.80 1.000000

Debit 331.80 1.000000

Debit 331.80 1.000000

Debit 67.20 1.000000

Debit 22.22 1.000000

Assuming last transaction is latest date, would MAC be Sum of amount / sum of qty?

Hi BB, in the case of calculating cost based on moving average, we’d only use the quantities and the credits (assuming these represent paying for the product). Any debits from sales of the product would not affect the cost.

Since all your credits in that example were -225.15, then the cost per unit is simply 225.15.

However, since there were only 4 credits and 5 debits, that leaves your stock in an overall quantity of -1.

So you’d need one additional credit in order for any system to properly calculate the cost.

Hi Thomas,

This is a great read!

I was wondering at what periods would you calculate the moving average in my case? For example if I make a new order, the invoices for manufacturing will be in January, inspection in February and freight is in March. When will you calculate the moving average? In January? I only have the manufacturing invoice and estimates of inspection and freight. Or in March? When I receive the goods and have all the invoices to calculate the moving average.

And assuming you calculate the moving average in March, does it prevent you from recording the January/February invoices in your monthly periodic bookkeeping system? Does inventory invoices even recorded into the bookkeeping system in any other way but as COGS when sales occurs?

Thank you!

Hi Tal,

Thanks for stopping by!

That’s a good question; you could record the cost initially in January and then update the PO/cost when you get other inspection/freight charges. Your other method would work too, but at least this way you have partial costs captured, even though you’re waiting for inspection/freight costs to arrive.

I can’t speak for all systems, but if you did this in inFlow Inventory, the product cost would be updated accordingly if you made changes to the original PO. The date used for the updated cost would be the Receive Date for those items on the purchase order.

how do I calculate my unit cost after my sales which has an increased sales cost to my new purchase?

Hi Zina, adjusting cost after-the-fact can be a bit tricky, but generally we suggest adding or modifying the sales order record and making a note of it, so others know why it was changed. In inFlow you can add extra services to the sales order to effectively increase the cost of items sold on that order.

Or if you’re using moving average cost within inFlow, you can add a retroactive cost adjustment to that product. This article can help you with that if you use inFlow Inventory: https://www.inflowdebug.com/support/cloud/my-products-cost-is-wrong-how-do-i-change-it/

That way any report that calculates profit will take this newer, higher cost into account.

If in the moving average inventory method, there are purchases with purchase discounts and allowances, how should we account for that?

Hi Mathia,

Our system (inFlow Inventory) actually recommends moving averages by default. If you make a purchase order and there’s a discount applied, it will automatically deduct from the cost of that product. You can even specify that certain items on a PO have a discount, while others were purchased at full price, and inFlow can account for all of them using the formulas in this article.